In a time now lost to history, there was a sharp definition between race cars and street cars. In today’s world of 1,000 hp “street” cars, that distinction has long since become nearly invisible. Streetcars easily skirt that line, yet bring it all back. This places a heavy load on drivelines, especially manual gearboxes and the clutch, whose job it is to transfer that power cleanly and efficiently.

The current version of the Dragon Claw is a twin-disc setup which combines the advantages of the diaphragm-style pressure plate with the centrifugal force benefits of the classic Long-style 3-finger clutch to produce a smooth-engaging street clutch that is capable of handling high horsepower and high rpm.

In that same crude time now past, a clutch assigned to lock onto 1,000 lb-ft of torque came equipped with monstrous spring-pressure and a clamp load that demanded gorilla-leg power or hydraulic-assistance for clutch release. But now in the 21st Century of performance there are a few techniques that can make holding massive power almost easy.

In the early days of clutch design, the three-finger clutch, also known as a Long-style pressure plate, used three sets of three coil springs to load the pressure plate using three narrow finger levers to release the load. The next innovation was to add weight to the very end of those fingers. Adding several grams of weight to the lever could add hundreds of pounds of force to the clutch – increasing the load on the clutch so it could hold additional power. These were (and continue to be) very good race clutches, but that lever load came at a price.

This is a race clutch you drive on the street, or a street clutch that you can race. -Ross McCombs on the Dragon Claw

For the street, these clutches offer rather significant pedal effort even at idle because coil springs present their highest load when compressed at full release. Conversely, a diaphragm spring – more accurately called a Bellville spring – works differently. This spring design places a static load on the pressure plate, but once the spring is collapsed past center, the load on the clutch pedal is greatly decreased, allowing the driver to hold the clutch pedal in with minimal effort. This design feature, along with the Belleville’s shorter travel is the reason most street clutches use a diaphragm spring.

But diaphragm springs suffer the inherent downside of weak clamp loads when attempting to use them in a street application where power levels are now sneaking up on four-digit numbers. That was the dilemma facing Ross McCombs. He is a long-time manual transmission artist who started Quick Time Bellhousings that is now part of the Holley Performance group. McCombs had a very healthy 2.8-liter Kenne-Bell supercharger on the Coyote engine in his early Mustang which he likes to autocross and take to track-day events. The existing street clutches he had tried were not holding up to the 800-plus horsepower his car lays down.

The weight of the entire Dragon Claw package is 35 pounds. The 6061-T6 aluminum flywheel is lightened near the outside circumference to reduce the power required to accelerate the assembly. The aluminum cover is forged from 7075 T6 to keep the weight down. A typical single-disc clutch assembly with a steel 35-pound flywheel is over 50 pounds.

Dual-disc clutches are the logical choice when facing big power, but McCombs wanted more. After studying the benefits of the three-finger Long-style pressure plate versus the advantages of the diaphragm, he decided to merge the two into what eventually became the dual-disc Dragon Claw.

McCombs realized adding a centrifugally-assisted lever arm would place additional load on the clutch discs with a more superior effort if placed on the outside edge of the pressure plate, where the weights could take advantage of the higher speed of that circumferential location. Plus, the three lever arms would load the discs while not adversely affecting pedal effort at high engine speeds.

The centrifugal force lever is designed to load the pressure plate with additional clamp-load with increasing force as rpm increases. This does not add to clutch-pedal force since the load is applied at the outside edge.

Because a diaphragm spring tends to engage rather abruptly, compared to a soft static-loaded Long-style, the Dragon Claw is not really aimed at the drag racing market. It can certainly be used and will survive in this environment, but McCombs says there are other clutch designs that would offer better advantages for ultimate drag strip clutch tuning.

The Dragon Claw was initially developed as a twin-disc unit with triple- and single-disc versions currently in the pipeline. McCombs sees the twin-disc as the ideal application for a street clutch assembly, which can easily handle power levels starting at around 500 horsepower on up while still being completely street friendly. He told us the current twin-disc system as shown in the accompanying photos is capable of handling around 1,200 hp while a single-disc package is good to 600 hp. The near-future, triple-disc version is aimed at those rocket fanatics with engines making 1,800 hp.

Both 10-inch clutch discs use spring-loaded hubs to soften engagement, along with segmented organic-ceramic pucks. These employ a proprietary material that offers both a high coefficient of friction yet street-friendly engagement.

Multiple-disc clutches are certainly not a new invention. In a simple, single-disc clutch there are three variables that affect the holding force between the disc, the pressure plate, and the flywheel. The three variables are clamp-load, the coefficient of friction of the clutch material, and the contact area of the clutch disc.

Obviously, we can increase the area of a single-disc by adding a larger disc but as power increases, diameters are limited by existing bell-housing sizes. We can increase the static clamp-load but this increases stress on the linkage and the effort required to compress the clutch pedal. The third variable is to increase the coefficient of friction – but this is problematic since higher-friction materials generally also make clutch engagement very abrupt – turning the clutch into an on-off switch which only makes the car difficult to drive.

Of course, a clutch is only as good as the rest of the system which includes the bell-housing. We’ve tested many aftermarket bell-housings that are off-register by 0.030-inch. Quick Time’s hydroformed bellhousings are usually within 0.002-inch. The measurements on this unit reveal it is well inside the 0.005-inch register requirement.

The key is to build a street clutch that will hold lots of power while also being easy to operate the clutch pedal and engage smoothly. That’s a tall order. But an easy way to increase capacity is to merely double the number of clutch discs. This automatically doubles the capacity. This also allows the designer to reduce the static clamp-load to reduce pedal effort, making it easier to use on the street.

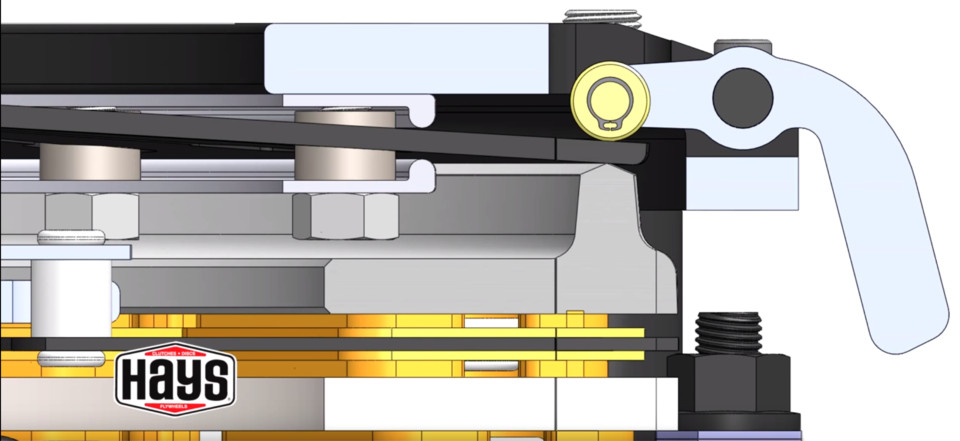

McCombs and the Hays engineers created an organic/ceramic puck material that offers both a high coefficient of friction, yet engages smoothly and requires no break-in period. But the real secret to the Dragon Claw is the centrifugal levers added to the pressure plate that increase the clamp-load at higher engine speeds. Essentially, when engine rpm doubles from 3,000 to 6,000, the Dragon Claw levers add roughly 1,000 pounds of clamp-load to ensure the discs don’t slip, as seen on the accompanying graph.

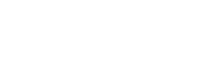

This Hays illustration reveals how the external lever puts additional load directly on the pressure plate. Increasing load improves the clutch’s ability to withstand high-torque input.

McCombs also mentioned that he designed this clutch especially for power-adder street applications. “No other diaphragm clutch with stock clutch-pedal effort will react fast enough under rapid acceleration to stop the clutch discs from glazing. As more and more forced-air-induction engines hit the street this clutch is a great answer to the problem.”

All of these are positive steps toward connecting a 1,000 hp engine to the transmission and eventually to the rear tires. But there is no free lunch. The complexity of the system is certainly something to consider, since we now have four friction surfaces instead of just two. Another point to consider might be the weight of the twin-clutch discs.

One advantage to a lighter clutch assembly on a road course or autocross is that instead of accelerating a heavy flywheel and clutch assembly, that power can be used to accelerate quicker off the corners. The Dragon Claw’s rotational weight is concentrated near the input shaft centerline which makes it accelerate quicker.

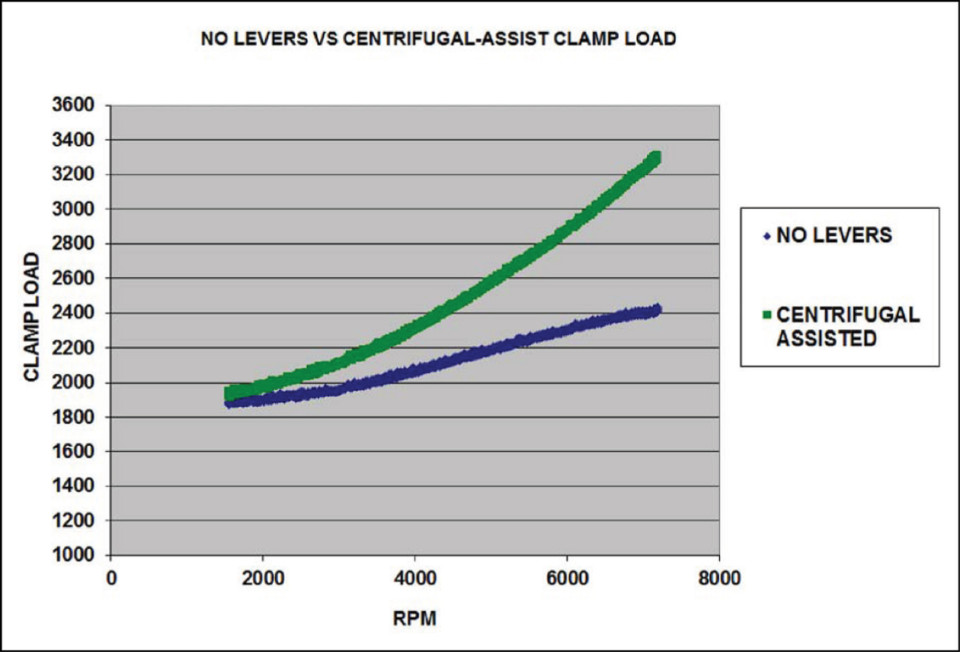

We disassembled the Dragon Claw and weighed all the components separately. Each of the two 10-inch clutch discs weighs four pounds apiece. Compare this to a larger 11-inch street clutch that comes in at about five pounds. This is a little more than a third more weight which is spinning at high speed when the clutch is released. This added mass will be significantly greater than a single-disc. This is important because this higher force will be more difficult for the transmission synchronizers to control.

To be fair to the Dragon Claw and all twin-disc clutches, its important to look at where the weight on the clutch discs is located. For the Dragon Claw discs, the majority of the mass is located near the center of each disc in the sprung hub assembly. You will note that the Dragon Claw discs use segmented pucks with considerable space between them and the actual hub is also segmented to reduce weight toward the outside of the disc.

This Hays graph shows the additional load created by engine speed on a clutch without the centrifugal assist (blue line) compared to more than 800 additional pounds added by the centrifugal-assist of the Dragon Claw (green line). Greater clamp-load means the clutch can hold more torque without slippage. The peak clamp-load is just over 3,200 pounds of force.

We questioned McCombs about this effect, and he says that in the several years he has run the Dragon Claw clutch during development in his autocross and road race Mustang, he’s never had a transmission or synchronizer problem.

Overall, the Dragon Claw is an innovative new clutch design that has applied proven concepts from earlier clutches and combined them in such a way as to give the big-power street cars a legitimate system that can get a grip on what increasingly is becoming a much more powerful world.

We placed both clutch discs on this Super T-10 input shaft to illustrate that any dual-disc clutch assembly will add more spinning force over a single-disc clutch and the transmission synchros will have to deal with this additional load.

Parts List:

This is a partial list of Dragon Claw dual-disc packages. Other applications are forthcoming.

| Description | PN | Source |

| Dragon Claw, dual, big-block Chevy | 96-101 | Summit Racing |

| Dragon Claw, dual, ’97-up LS | 96-105 | Summit Racing |

| Dragon Claw, dual, small-block Chevy, 2 pc main | 96-100 | Summit Racing |

| Dragon Claw, dual, 2011-’14 Mustang | 96-201 | Summit Racing |

| Dragon Claw dual, 1981 – ’95 5.0 Mustang | 96-210 | Summit Racing |

| Dragon Claw dual, 2009-’10 5.7/6.1/6.4L Challenger | 96-301 | Summit Racing |